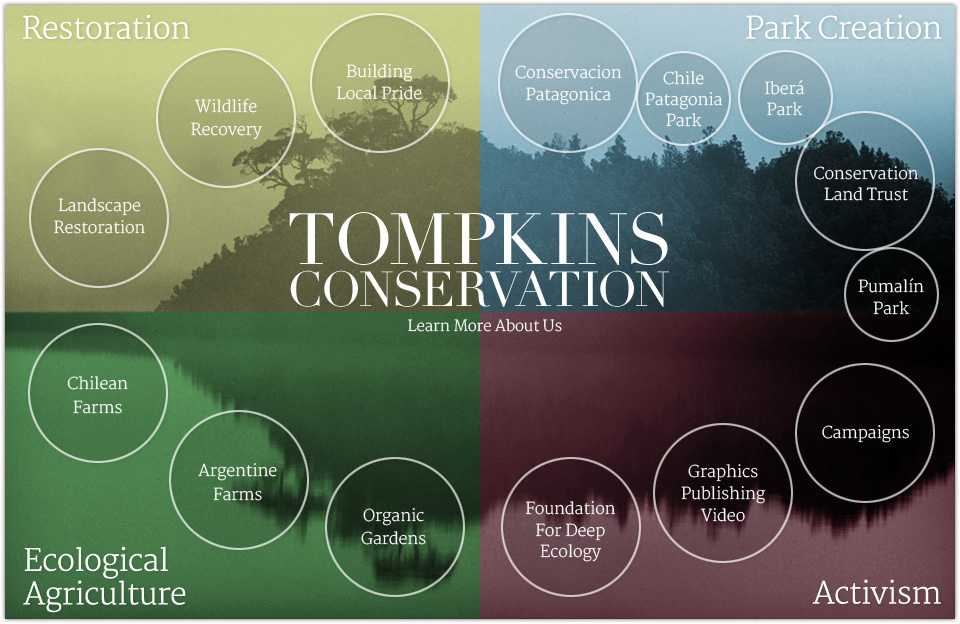

Douglas Tompkins (1943-2015) was a mountaineer, Deep Ecologist, conservation activist, lover of nature, and textile entrepreneur, founder of Esprit and North Face. A footloose entrepreneur turned activist, after starting two global clothing brands, Tompkins renounced the ecologically unsustainable fashion industry and moved his assets and passions to South America, where he proceeded with Kristin Tompkins (neé McDivitt) to make the greatest land conservation purchases of any private individuals on earth. For their tireless conservation work, Douglas and Kristin received the 2015 Global Economy Prize from the Institute for the World Economy, at Kiel University, my alma mater.

While many nay-sayerying environmental justice academics, salmon fishery owners, loggers, and nationalists decry Tompkins’ environmental conservation as a new wave of green imperialism, Tompkins, after suffering such attacks in Chile following his purchase and gift of Parque Pumalín to the Chilean people as a protected national heritage sanctuary, those following the Tompkins’ legacy from a less partial point of view cannot help but acknowledge his enormous contributions to current and future generations.

Tompkins took pains to reconcile differences, to ask for forgiveness as an American foreigner in Chile, and as a rabble-rouser sparking Chile’s environmental movement in a resource exploitative economy. Generously compensating peasants and squatters who had taken up residency in public rainforest lands, Tompkins’ political enemies often charged him–falsely–with unfairly displacing Chileans for fortress conservation. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Parque Pumalín, Tompkins’ flagship gift to the Chilean people and to humanity for generations, is a pristine ecology filled with rare species and containing numerous biomes. It is one of the last places on earth of its kind, and incorporates in organic farms to supply food for visitors and jobs for locals. In creating the farms, Tompkins created buy-in and business opportunities for the local struggling community, which before was largely based on small-scale timber extraction. This sustainable model replace the previous unsustainable model, and brings recognition and orgullo to Chile as a protector of global patrimony.

Learning about his death earlier this year was particularly impactful for me, as it was back in Santiago de Chile in 2002 at age 21 in a Pontificia Universidad Católica course on Environmental Politics that I first learned of Tompkins and the type of conservation work he was engaged in in Chile.

While I was in Chile, studying abroad during my undergraduate years at UC Berkeley, I was working at the Facultad Latinoamericano para las Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) in Santiago, and learning about Tompkins’ work in the Palena province (XII) inspired me to shift into environmental political theory, which grew into my love for environmental philosophy and ethics, and eventually philosophy of biology. If it weren’t for my teachers in that Environmental Politics course at la PUC, and doing that report on the conservation movement and that controversial fellow Douglas Tompkins, I would never have attended the Rio +10 conference in Johannesburg, South Africa as UC Berkeley’s student delegate that following summer, and I would never have the insights, passions, and life path that I inhabit today. For Douglas Tompkins good work on this planet and the inspiration I found in his life’s work, I will always be grateful.