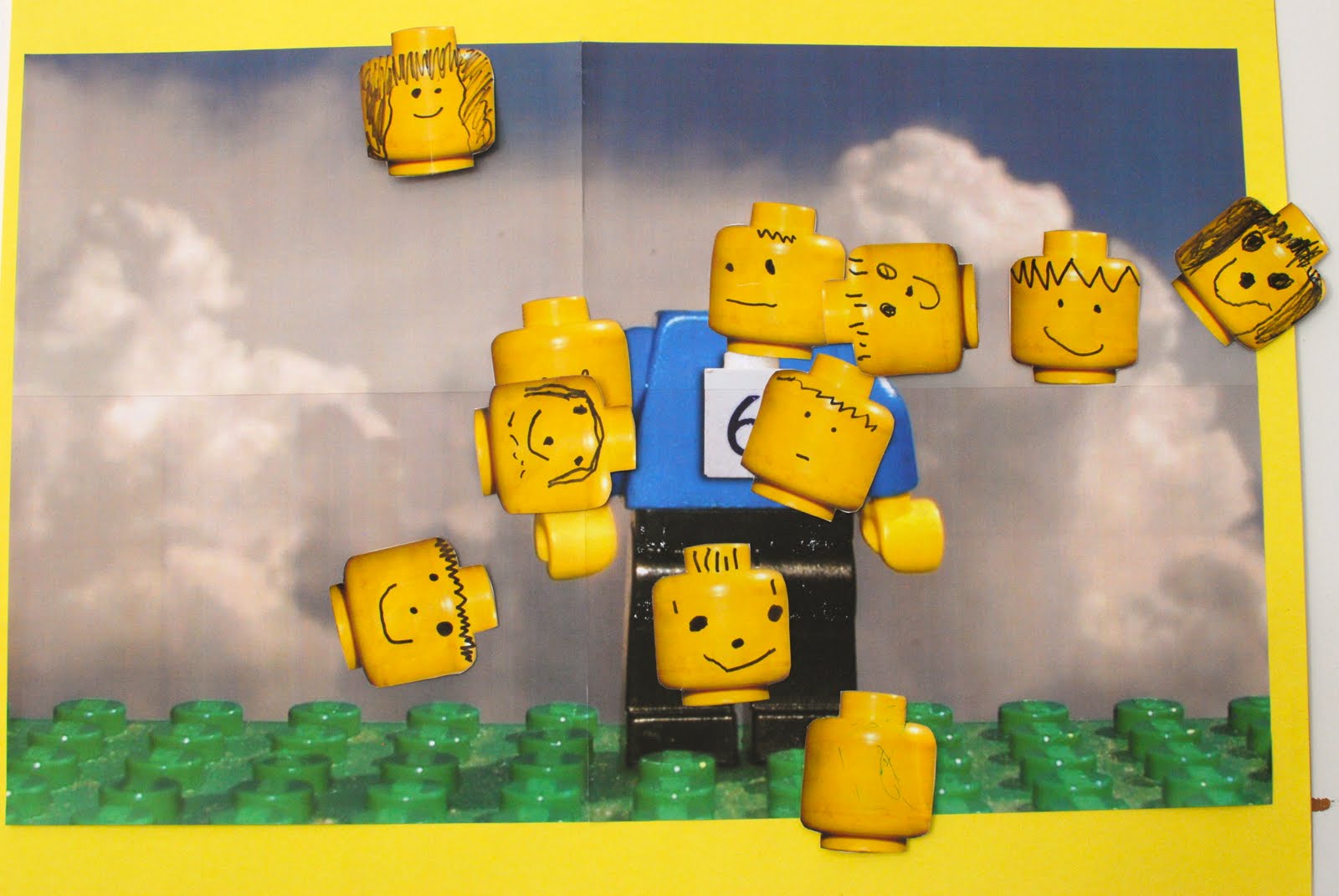

My kid doesn’t play with Legos the way that Lego wants you to think that people build Legos.

Instead of those lush displays with those thousand dollar co-branded sets with odious media corporations that only have pieces that you can use in one way once and then it’s not really usable again for just playing and improvising and making your own stuff, my kid makes Franken-lego disturbing constructions. A reason for this, is because I’ve actually never bought a set of Legos for my son. When I was a kid all the pieces interlocked so if you bought a set it would transfer to your overall larger collection of pieces to be used for an infinite number of future builds. But now the pieces don’t really work that way. Instead I see my son looking at the collection that we inherited, and he regularly asks why the Lego men and women – Lego people – are missing their arms or hands or heads. It seems like an aberration to him, and so he always asks why.

He asks why because obviously nothing in nature is piecemeal snaps together or is take-apartable; it doesn’t work that way. So when he’s asking questions about why does this guy have no hands or why does she have no head and he instead just snaps on a computer console piece where the head should be, it makes me understand how deeply ingrained in our society is a mechanistic view of the universe. The idea that it’s all disposable and interchangeable. This is the metaphysics on which Western philosophy and engineering is based on. It’s an engineering view of the world. But nothing living works that way, so there is a discrepency. And that’s why my three-year old is puzzled and disturbed by these missing parts; precisely because they point out that in life, nothing is simply missing.

Previously, no doll simply was toted around without their head unless there was a very intense story about how it got that way. Now we’re able to open cognitively to chimeras of all sorts, because almost all interactions in our lives are based on this hybrid interchangeability, a instrumentalization of everything. Technomedicine tries to accomplish the same interchangability of parts. Replace this organ here (never mind who it comes from, or what black markets exist for some entitled person who blew their kidneys or liver out from years of abuse), get an artificial heart there. If we are not the body, as the Cartesian metaphysics of mis-interpreted Christianity claims, then, you can hack up the whole thing and sew it back together however you please with no remainders.

Of course the shadow side of this, is that nothing has any value if it can just be exchange for something else. No matter how much you can exchange it for, if it is exchangeable and bollocks to the remainder, there is lacking certain forms of value, even if it might have a different sort of value and exchange economy. But it’s important to not collapse these two different types of value into one. Value is contextual. My heart is uniquely clocked to the rest of my body. My hands bear the battle scars of my events and decisions. The tenderness in their weaknesses would not be valued if they were given to another – those sentimental reminders would be interpreted only as weakness, not as years of service.

Thus, the things we play with, engage with, on an everyday basis, form the models we hold for how to treat people and the rest of nature. If our models are fragmentable and fragmentizing, it is all too easy to believe that such fragmentation, such dispensibility and replaceability, is an innate quality of reality, and that life is reducible to things that can be swapped out. If we take this view, we have grasped but half of reality, the digital code aspect, and ignored the analog, the gestalt, the élan vital, which is irreducible to mechanics. We need better toys to represent these aspects of reality, so that we’re not just coding for solely left-brain halls of mirrors, feeding back to us a fragmented self and reality.