An open-access book, Eco-Social Contracts for Sustainable and Just Futures edited by Patrick Huntjens, Najma Mohamed, Katja Hujo, Manisha Desai was just published, including a chapter Varieties of Eco-Social Contracts in Japanese Ecovillages and Coliving-Coworking Arrangements I co-authored with professors Yuho Hisayama (Kobe University) and Kazuhiko Ota (Nanzan University).

This research examines how contemporary Japanese ecovillages are reimagining the relationships between humans and nature, individual and community, work and life. Through ethnographic research, interviews, and site visits across Japan, we explore how these intentional communities are developing new eco-social contracts that challenge dominant paradigms of consumption, alienation, and ecological destruction.

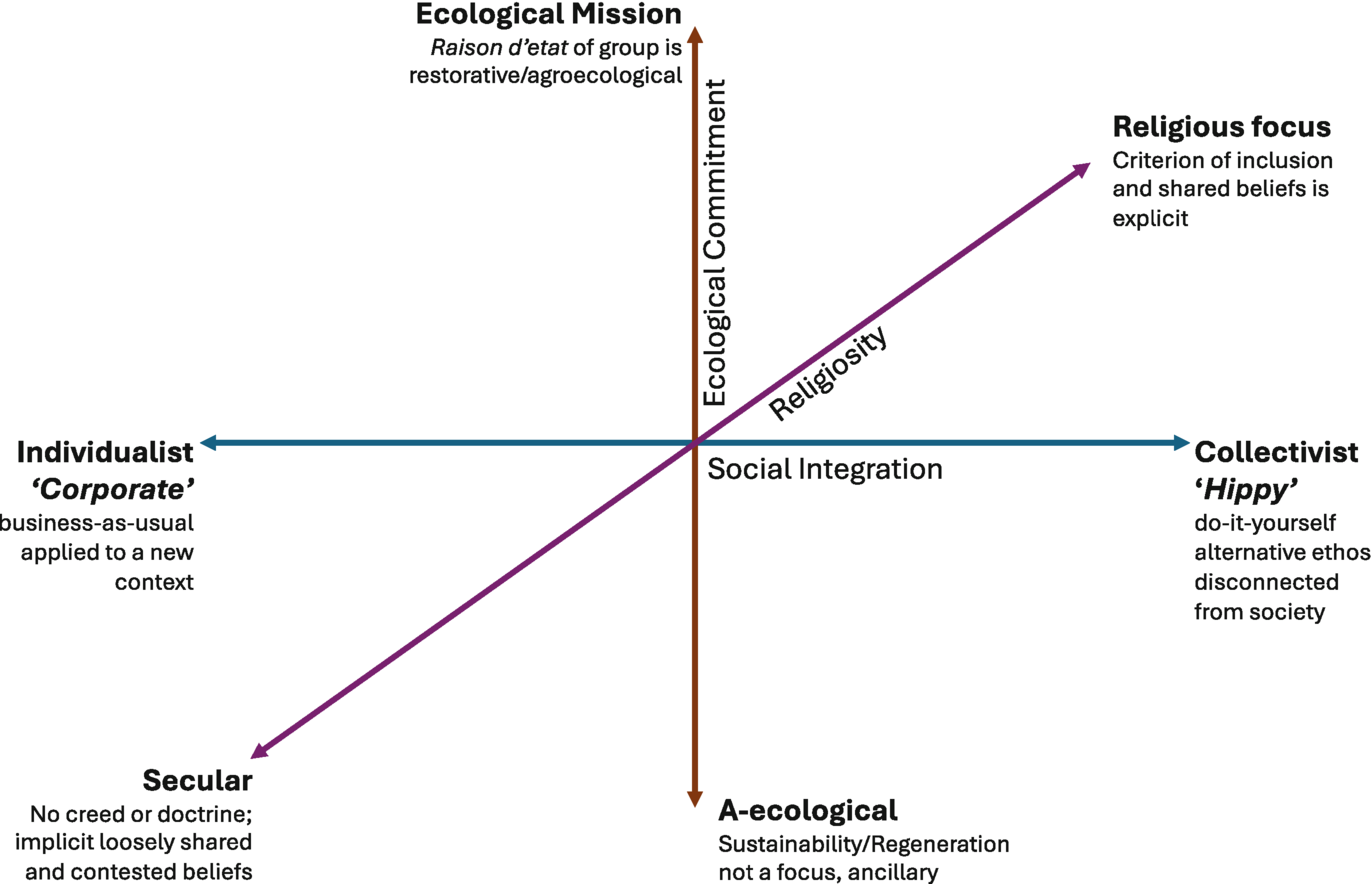

Our study reveals that Japanese ecovillages exist along multiple spectra — from secular to spiritual, token to thoroughgoing ecological commitments, individualist to collectivist, and system-compliant to off-the-grid experimental. We document communities ranging from corporate headquarters relocating 1,200 employees to rural Awaji Island under sustainability auspices, to small permaculture-inspired farming communes like Dana Village in Fukushima Prefecture, which produces 90-95% of its food on just one hectare of land. These diverse models reflect different approaches to addressing the polycrisis of climate change, inequality, and social fragmentation. Some ecovillages, like As-One in Suzuka, emphasize non-domination and cultivating intrinsic motivation for service without mandating work or compensation. Others draw explicitly on traditional satoyama (mountain farming) and satoumi (sea village) principles that historically provided nearly complete self-sufficiency through low-impact, multigenerational land stewardship.

A central finding of our research concerns the role of precipitating events in catalyzing alternative living arrangements. The March 11, 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster profoundly reshaped Japanese attitudes toward sustainability and community resilience. Many ecovillage founders were galvanized by this catastrophe to create alternative lifestyles that reject the systems enabling such predictable accidents. This demonstrates how crises can jolt people from status quo thinking, while inherited traditions like satoyama offer scaffolding for emergent practices. Together, these dynamics create conditions for reconfiguring social and ecological relations in ways that empower care relationships over extraction and domination.

The research also reveals inherent tensions and challenges facing ecovillages. Communities must navigate the paradox of building alternative worlds while integrating with surrounding populations still embedded in globalized habits. They require material resources and capital to approach self-sufficiency, yet seek to escape money-economy dependencies. In contrast, successful ecovillages like maintain longevity by actively engaging external partners, incorporating nonprofit structures, and cooperating with local communities. Our findings suggest that psychological, social, and ecological isometry — alignment across these dimensions — proves crucial for creating and maintaining viable ecovillages.

This research contributes to understanding how eco-social contracts can be practically reimagined and enacted at the community level. Japanese ecovillages demonstrate that prioritizing communal wellbeing over individual competition, and developing practices that meet evolutionary needs for recognition and belonging without strict hierarchy, can create partnership rather than dominating societies. While challenges remain — including potential gentrification, regulatory obstacles, and the risk of romanticizing traditional models — these experiments in living offer vital insights for addressing the interconnected crises of the twenty-first century. By creating liminal spaces where existing economic and environmental relations are set aside, ecovillages provide commons for exploring alternative ways of relating with self, other, and nature. As economic precarity increases globally and viable options within default systems continue to diminish, such models of ecological coliving and coworking will likely become increasingly attractive, not only in Japan but worldwide.